#MuseumFromHome

True art is imperishable and the genuine artist feels sincere pleasure in real and great products of genius.

Beethoven to composer Luigi Cherubini, 1823

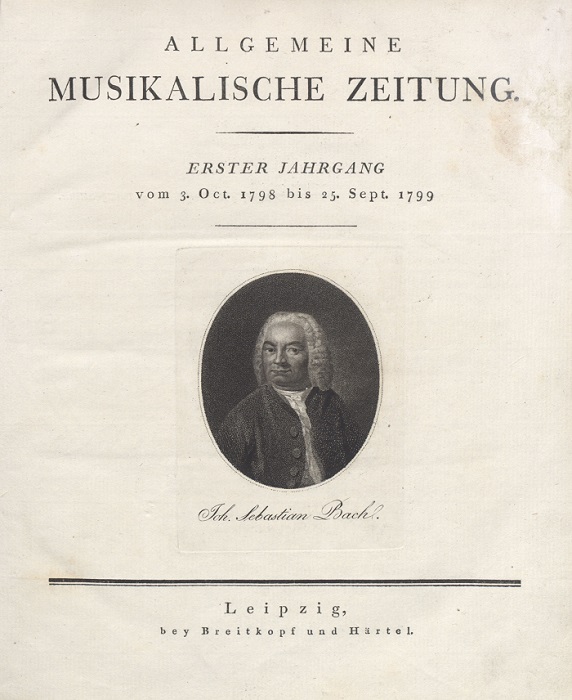

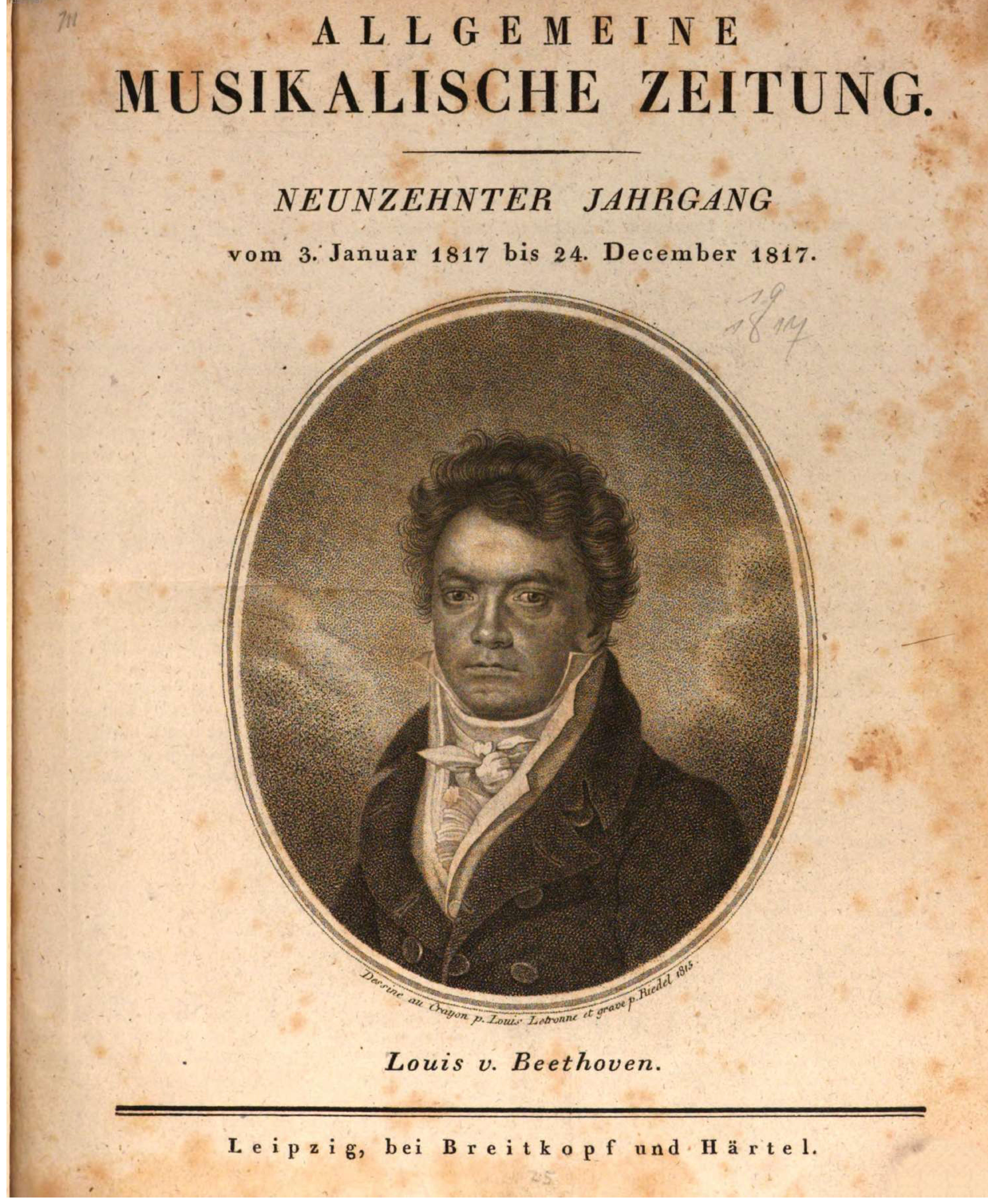

Nowadays, Beethoven and Bach are two of the world’s most famous composers. But how did they in particular come to be regarded as masters of classical music? And what made their compositions classics? A key role in this was played by Leipzig music periodical Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (AMZ) founded in 1798.

Initially, Beethoven’s music was regarded as radical, bewildering, even upsetting. However, AMZ explained Beethoven’s works and helped its readers throughout the German-speaking world to understand his music. Moreover, experiencing Beethoven’s music also nurtured new interest in Bach’s compositions. The history of 18th-century music dominated by the opera was reinterpreted in authoritative essays in AMZ as a history of instrumental music from Bach to Beethoven. And for the first time, a ‘canon of classical masterpieces’ emerged.

This exhibition illustrates the canonization of Bach and Beethoven as unsurpassed composers using the example of Leipzig, a bastion of musical in in the early 19th century. It also shows how Johann Sebastian Bach’s music influenced Beethoven’s style of composing.

Beethoven’s music sets in motion the machinery of awe, of fear, of terror, of pain, and awakens that infinite yearning which is the essence of Romanticism.

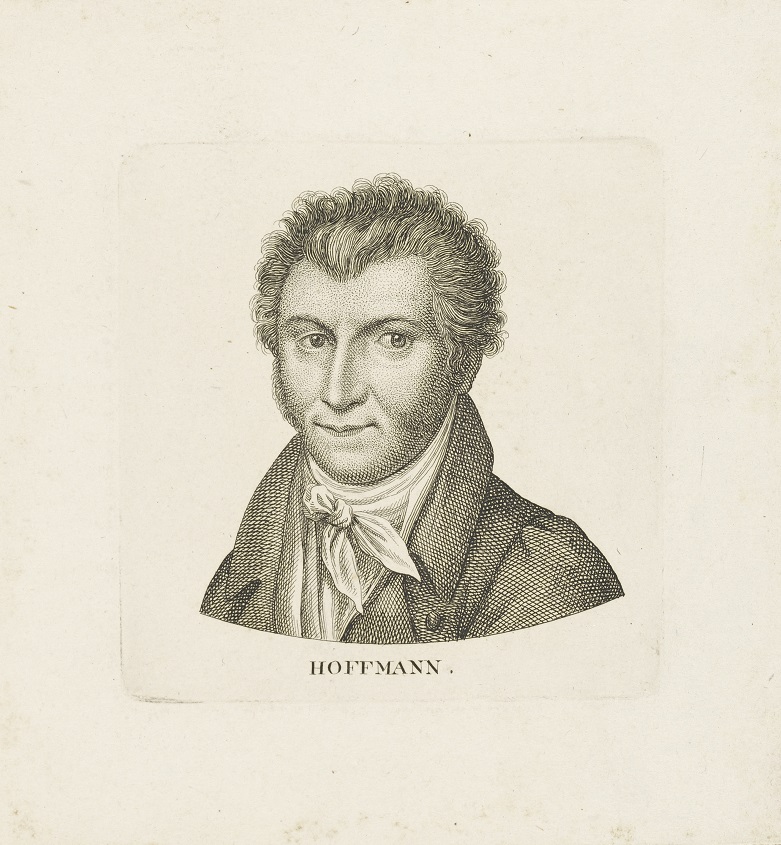

E.T.A. Hoffmann, Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, 1810

In 1798, writer and composer Friedrich Rochlitz and music publisher Gottfried Christoph Härtel founded Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (General music newspaper) in Leipzig. This, the foremost German music journal of its day, was aimed at a 'mixed audience' of experts and aficionados. As well as carrying reviews of contemporary music, it addressed aspects of philosophy and the history of music.

One of its writers was the famous author and composer E.T.A. Hoffmann. In his writings, he developed a new form of musical aesthetics that gave priority to instrumental music. His review of Beethoven’s 5th symphony shaped the image of Beethoven in the 19th century. He wrote that Beethoven’s instrumental music opened up 'the realm of the monstrous and immeasurable.' In it were 'giant shadows … destroying everything inside us, albeit not the pain of infinite yearning'.

E.T.A. Hoffmann described Mozart and Haydn as 'the creators of modern instrumental music' – and Beethoven as its perfecter. By creating the character of musical director Johannes Kreisler, he transported 'Sebastian Bach, the mighty genius' into the world of Romanticism.

I prefer your business above all other German publisher.

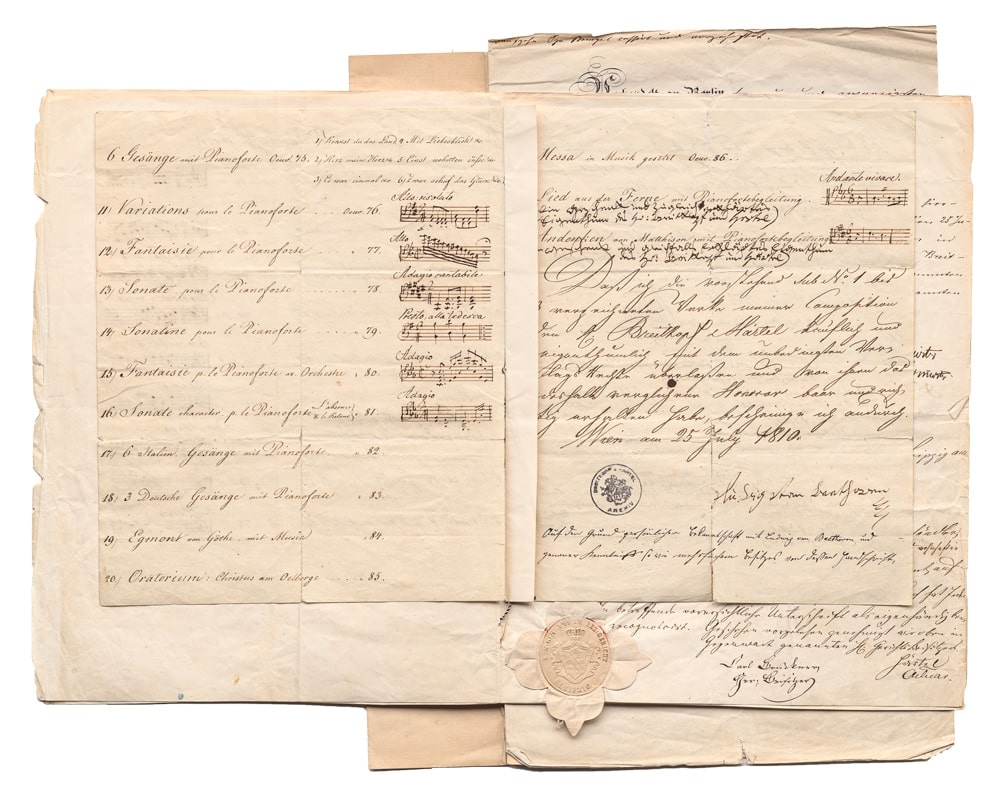

Beethoven to Gottfried Christoph Härtel, Vienna 1810

Being a freelance composer, Beethoven worked with various publishers, and skilfully negotiated fees for the rights to print his music.

Beethoven worked closely with two Leipzig music publishers. Bureau de Musique owned by Franz Anton Hoffmeister and Ambrosius Kühnel (later renamed Edition Peters) published first editions of several of his works, including his 1st Symphony and his 2nd Piano Concerto (both 1801). From 1802, he also had his music published by their rivals Breitkopf & Härtel, who became Beethoven’s main publisher between 1808 and 1812. All his compositions from Opus 67 (5th Symphony) to Opus 86 (Mass in C major) were published by Breitkopf & Härtel.

Beethoven also bought sheet music and books from Leipzig publishers. Breitkopf & Härtel supported Beethoven’s career by publishing Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung and from 1817 regularly sent him free copies of the journal.

Just as Italy has its Naples, the Frenchman his revolution, the Englishman his merchant marine, so the German has his Beethoven symphonies.

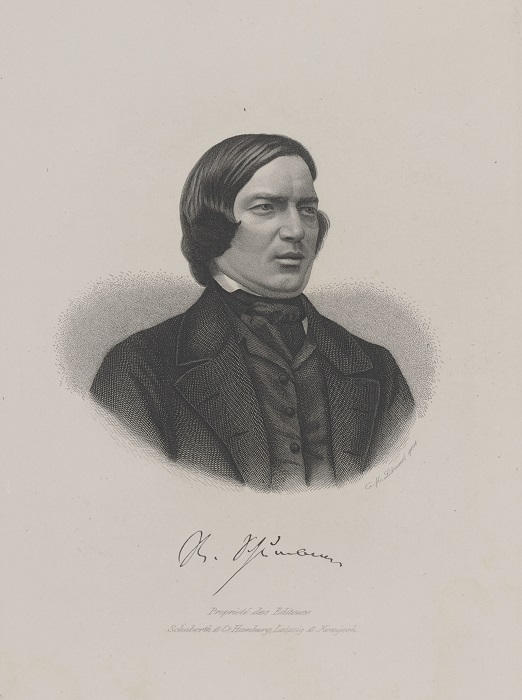

Robert Schumann, Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, 1839

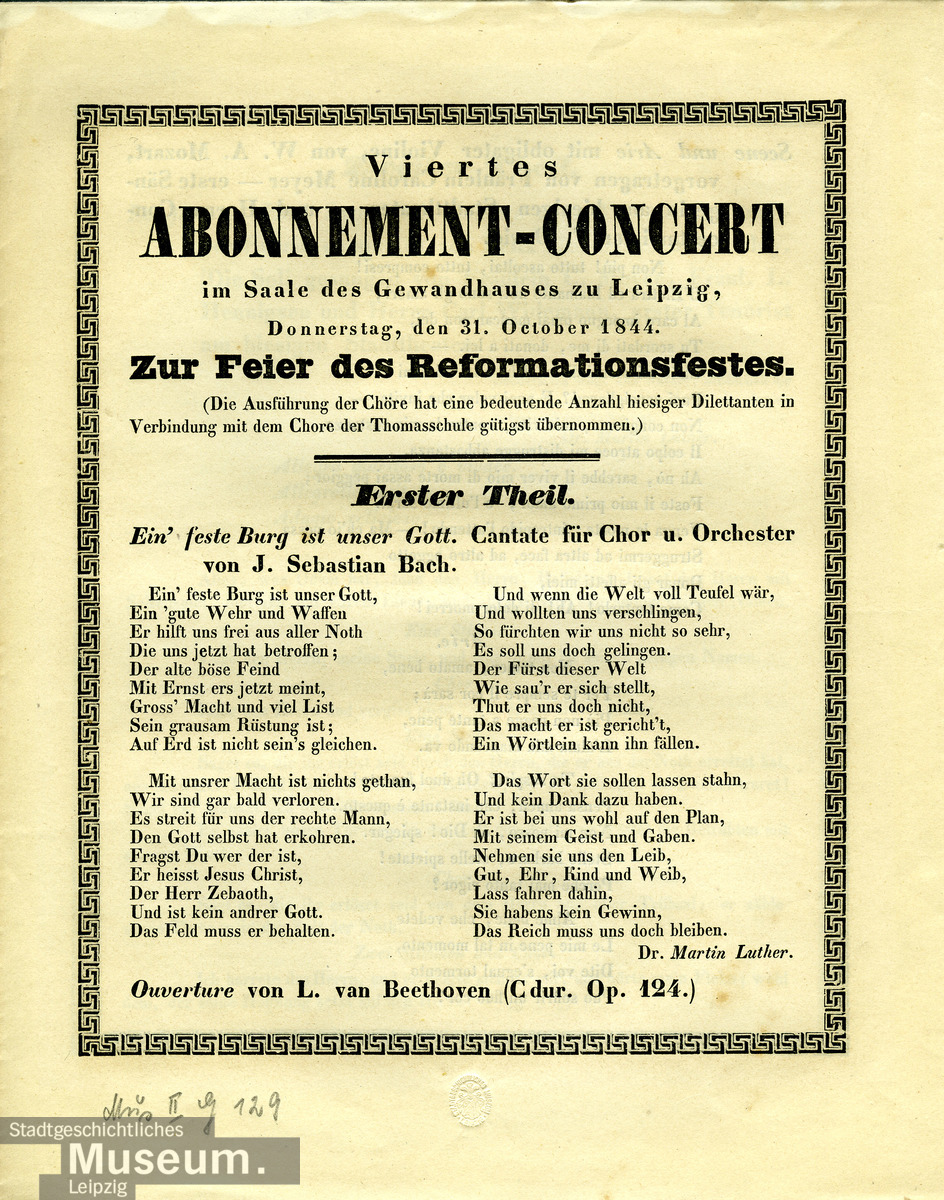

The Gewandhaus Orchestra has a long heritage of playing Beethoven’s music. Now the oldest non-royal orchestra in the German-speaking world, it was founded in 1743 by merchants and musicians from Leipzig. In 1781, it moved into its permanent venue in the Gewandhaus (a building used by textile merchants) and gave some twenty subscription concerts annually as well as performances of chamber music and special concerts.

Beethoven has been part of its repertoire since 1799. Two compositions by Beethoven were even first per-formed in the Gewandhaus. According to AMZ, the Triple Concerto for Piano, Violin and Cello on 18 February 1808 went down 'only moderately' with the audience. By contrast, the 'very large audience' was thrilled by his 5th Piano Concerto on 28 November 1811. In 1825/26, the Gewandhaus Orchestra performed all nine Beethoven symphonies in the same cycle for the first time anywhere in the world.

In addition to contemporary music, works by Mozart and Haydn were often played by the Gewandhaus Orchestra. In 1838, conductor Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy introduced the Historical Concerts, at which music by Johann Sebastian Bach and other great composers of times past was regularly performed. These works were usually arranged for 19th-century instruments.

Honour the old, but bring a warm heart to what is new. Do not be prejudiced against unknown names.

Robert Schumann, in: Musikalische Haus- und Lebensregeln, 1848

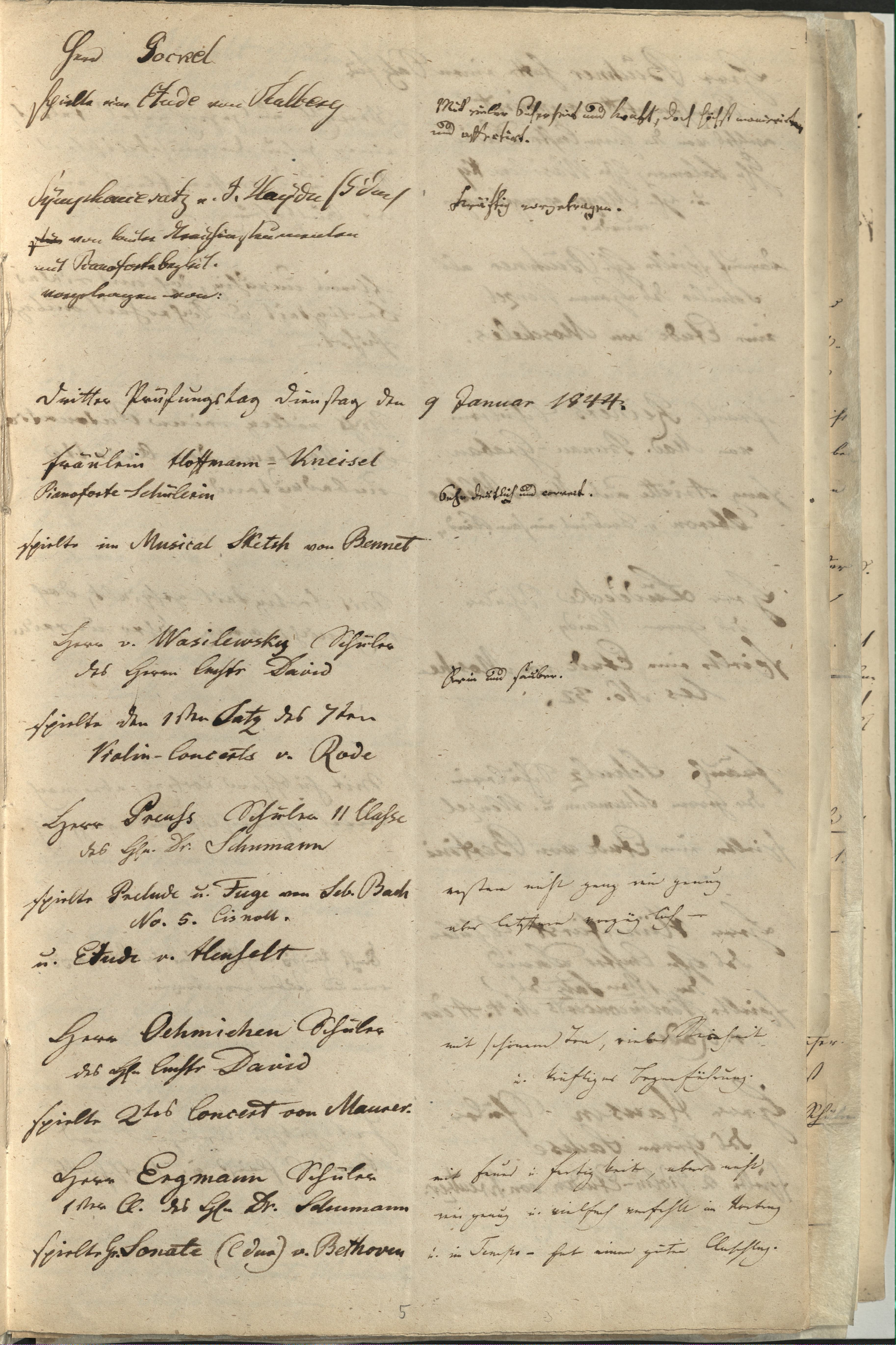

Until the mid-19th century, there were no permanent institutions for the training of professional musicians in Germany. In 1843, Felix Mendelssohn founded Germany’s first conservatory of music in Leipzig. Among the teaching staff were Moritz Hauptmann (the cantor of St Thomas’s Church; he taught music theory), Ferdinand David (the Gewandhaus concertmaster; violin), Carl Ferdinand Becker (the organist at St Nicholas’s Church; organ, history of music), Ernst Friedrich Richter (the director of Leipzig Singakademie; harmony and composition), and the composer Robert Schumann (piano, composition and score-playing).

Judging by examination records, sheet music and textbooks, music by Bach and Beethoven featured prominently in teaching from the outset. For example, Robert Schumann’s students performed preludes and fugues from Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier and Beethoven’s sonatas. Ernst Richter based his study of musical form on many examples taken from Beethoven’s works. Meanwhile, Ferdinand David published Bach’s 'violin sonatas solely for use at the Conservatory of Music'.

How the heavenly thoughts of my dearly beloved Beethoven appear to me ever higher, in an ever purer, sublime light!

Henriette Voigt, diary, 27 June 1831

There was a vibrant music scene in Leipzig thanks to choirs and musical societies performing in townhouses, gardens, inns, public halls and churches. Professional and amateur musicians as well as composers worked closely together.

The private chamber music recitals by the pianist Henriette Voigt frequently included violin sonatas by Bach and Beethoven along with Beethoven symphonies arranged for piano four hands. Meanwhile, the singer Livia Frege gave performances of lieder, operas, and music for choir and orchestra in her salon. She performed Beethoven’s opera Fidelio as well as Bach’s Mass in B minor with her own choir and musicians from the Gewandhaus.

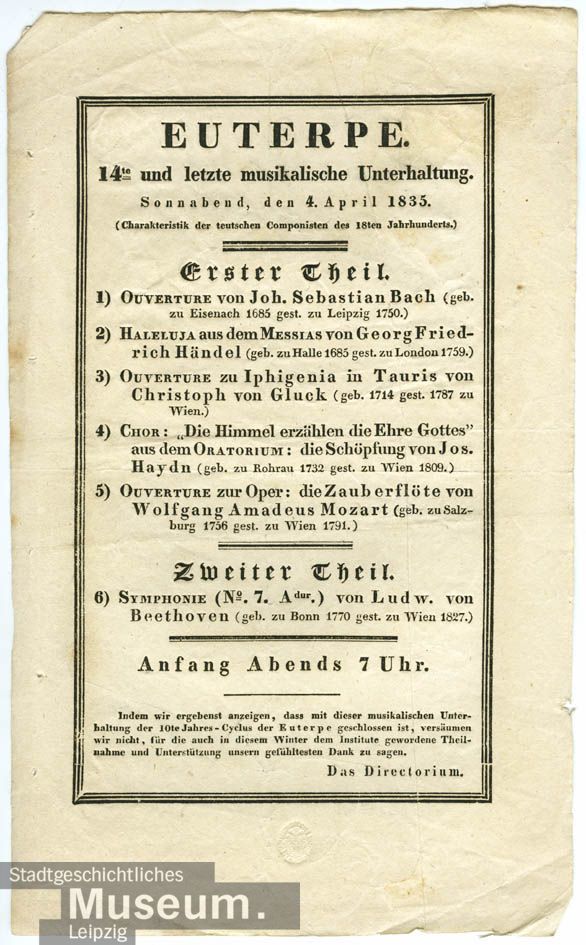

The Euterpe orchestral society founded in 1824 regularly performed Beethoven’s symphonies and overtures at its concerts. Three years before the start of the Historical Concerts at the Gewandhaus, Euterpe hosted a concert programme on 4 April 1835 spanning the musical history of the 18th century from Bach to Beethoven.

Ludwig van Beethoven was already famous in his lifetime. In 1823, publishers Breitkopf & Härtel commissioned Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller to paint a portrait of Beethoven. The oil painting was frequently reproduced for people’s living rooms in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The original portrait was destroyed by a fire at the publishing house during the Second World War.

Playing the piano was part of the educational aspirations of many middle-class families in the 19th century. Young girls and ladies in particular were expected to entertain guests musically at social gatherings. Countless popular piano pieces were written for this purpose, many of which have been forgotten. By contrast, Beethoven’s piano works for aficionados, such as the famous ‘Für Elise’, became classics.

In addition to sales of sheet music, piano manufacturing also experienced a huge upswing. From 1807 to 1872, publishers Breitkopf & Härtel built upright and grand pianos in their own workshop, establishing the tradition of piano-making in Leipzig.

Fig.

Ludwig van Beethoven, Steel engraving after a painting by Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, Leipzig, mid-19th century, Beethoven-Haus Bonn

https://da.beethoven.de/sixcms/detail.php?id=&template=dokseite_digitale...

J.S. Bach was a magnificent old chap. We want to erect a small monument to him here outside St Thomas’s School.

Felix Mendelssohn to Karl Klingemann, early 1838

The first monuments to Bach and Beethoven were erected almost simultaneously. In 1843, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy had a memorial to Bach put up in Leipzig and Bach's grandson took part in its festive dedication. Meanwhile, the monument to Beethoven in Bonn unveiled on Münsterplatz in 1845 was the result of a campaign by August Wilhelm von Schlegel and the Bonn Association for the Beethoven Monument.

In 1850, the Bach Society was founded in Leipzig with the aim of producing a complete edition of his works. The enormous editions of the works of Bach (1851–99) and Beethoven (1862–88) published by Breitkopf & Härtel enabled people to comprehensively study the two composers’ output for the first time.

The discovery of Bach’s presumed grave in St John’s cemetery in Leipzig in 1894 spurred plans for a new Bach monument. It was erected in 1908 by Carl Seffner outside St Thomas’s Church. Meanwhile, Max Klinger illustrated Beethoven’s epochal impact in his sculpture of 1902, which was inspired by Phidias’s ancient statue of Zeus at Olympia and depicted the composer as a godlike reinventor and master of music.

Fig. 1

The Old Monument to Bach outside St Thomas’s Church , after a watercolour by Eduard Bendemann, c.1850, Wood engraving, 1858, Bach-Archiv Leipzig

Fig. 2

Unveiling of the monument to Beethoven on Münsterplatz in Bonn on 12 August 1845, Wood engraving, Beethoven-Haus Bonn

Fig. 3

Max Klinger working on ‘Beethoven’, Anonymous, photography, before 1902, Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig

Beethoven studied Bach’s music throughout his life, even though at that time it was only familiar to a few specialists. When he was just twelve, he could play the preludes and fugues from The Well-Tempered Clavier. He explored Bach’s elaborate compositional style, made transcriptions and arrangements of Bach’s music, and acquired printed editions of his works. In 1801, for example, he subscribed to the complete edition of Bach’s keyboard works published by Hoffmeister & Kühnel in Leipzig. And in 1810, he asked Breitkopf & Härtel to send him Bach’s Mass in B minor. Beethoven’s collection of sheet music also included The Art of Fugue, prompting him to compose his Great Fugue in 1825.

Bach’s music influenced Beethoven’s works than on almost any other composer. It inspired him to deepen his work on motifs, adopt a new approach to harmony, and radically expand his expressiveness. Bach’s influence is audible in many of Beethoven’s works, especially his late piano sonatas and string quartets as well as his famous Missa solemnis.

UNESCO added Beethoven’s 9th Symphony to its Memory of the World Register in 2001, followed by Bach’s Mass in B minor in 2015. In doing so, it recognized the pioneering significance of the complete works of both composers for humanity.

Back in 1818, publisher Hans-Georg Nägeli had described the Mass in B minor in AMZ as the 'greatest musical work of art of all times and nations'. Bach worked on it until the end of his life. By setting the text of the Latin mass to music, he created a deeply moving interdenominational work of timeless validity from the imploring Kyrie (‘Lord, have mercy’) to the prayer for peace ‘Dona Nobis Pacem’.

Beethoven’s 9th symphony with its final chorus ‘Ode to Joy’ has become a symbol of humanity and freedom. In 1985, the melody of ‘Ode to Joy’ was adopted by the European Community as its official anthem. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Leonhard Bernstein conducted the symphony in Berlin on 25 December 1989, changing Schiller’s opening words 'Joy, beautiful spark of divinity' to 'Freedom, beautiful spark of divinity'.